Prince of Persia is an action platforming video game from 1989, created by a team consisting only of fresh out-of-college Jordan Mechner, with some support from friends, family and his publisher. His brother was roped in to do acrobatics on camera, serving as reference material for the animations in the game, while his father is credited as the music composer. The Making of Prince of Persia gives a behind the scenes look into how the game came to be, from conception to computer code, including Jordan Mechner’s day-to-day journals and design sketches.

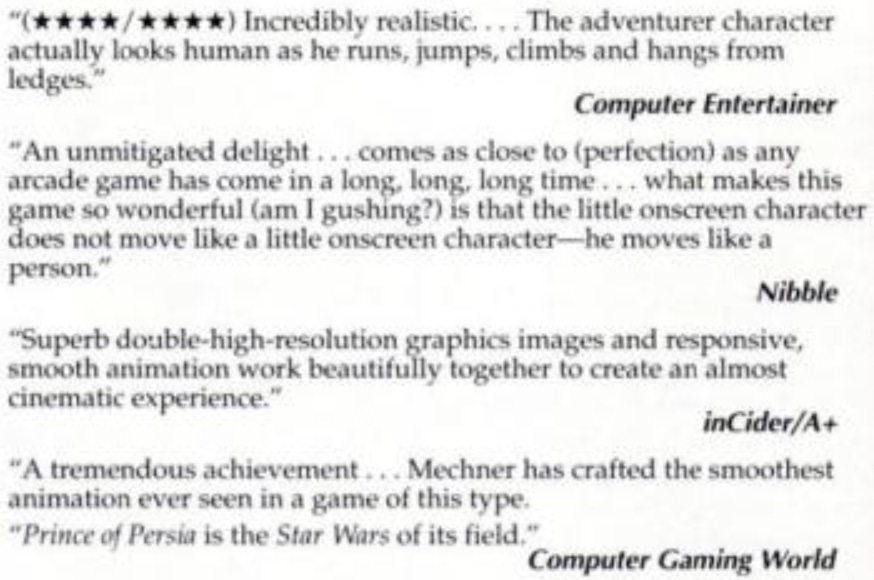

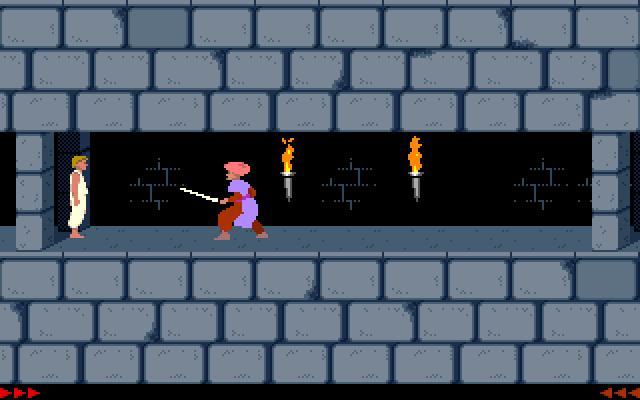

To establish the necessary context, I will summarize the game that the book documents the making of. It is not really possible to convey the feel of the gameplay, but fortunately, Prince of Persia is a game of many qualities. On release, the game was widely praised for its graphics, but these are obviously less impressive by modern standards. In my opinion, the secret sauce of Prince of Persia is the highly evocative scenes, which makes for some good 320x200 pixel screenshots and GIFs.

[Advertisement, Computer Gaming World N. 79: contrast adjusted from source https://popuw.com/magazines.html]

Why should you care about video games at all, let alone this particular historical artifact and the somewhat angsty diary of a twenty-five year old? I will resist the temptation of pretending that video games are important. Let me just suggest that, of all that is useless and fascinating, video games are perhaps not only the most useless, but also the most fascinating. If you haven’t called your best friend in a month or if your kitchen is on fire, I would recommend attending to those matters first. Otherwise, let me try to draw you in with some classic logical fallacies:

Appeal to authority: "The engineer in me loved his description of the technical challenges and solutions, and the entrepreneur in me loved the honest chronicle of his emotional adventure." — Mike Krieger, co-founder of Instagram

Argumentum ad populum: Prince of Persia gave rise to a franchise, including a series of highly successful console games and a Disney movie starring Jake Gyllenhaal (it’s not a great movie - Jordan Mechner wrote the original story before it was passed through three different screenwriters in a game of Chinese whispers).

Yeah, well, that’s just your opinion, man: The Making of Prince of Persia is an unusually honest first person account of how a masterpiece is cobbled together, from barely a germ of an idea through a no-fun technical demo to a widely acclaimed masterpiece. Sometimes the real story is the missteps and self-criticisms we made along the way.

No, seriously, you can’t just make things up and expect me to believe you: Prince of Persia is a tour de force of video game narrative. There are many games that tell good or even great stories by use of words, words, words in the form of dialogue and narration interleaved with the actual gameplay. Prince of Persia contains only a hundred words (approximately the length of this paragraph), all in a framing story. Nonetheless, its gameplay tells a simple and evocative story.

The Game of Persia

How to defeat the vizier and rescue the princess in less than sixty minutes

Prince of Persia is a platforming game, superficially similar to the old Mario games. However, aside from laboriously climbing between the floors of the level, movement is limited to the horizontal axis, consisting of running and jumping. This simplified platforming frees up some so-called design space that Mechner fills with exploration and combat elements: unlike in Mario, you don't complete levels by just going left-to-right (level design is a bit like the simpler ghost house levels in Super Mario World), and unlike in Mario, you don't defeat guards by jumping on top of their heads (the sword works better).

I will mostly try to highlight how the game and level design integrates story beats, mini-puzzles and cinematic set pieces without breaking out of the normal gameflow (no quick time events!). It's worth keeping in mind that Prince of Persia has very generous input buffers. This is like auto-aim for platforming - you can make pixel-perfect jumps and knick-of-time sword parries without perfect timing. This is relatively common in modern games, particularly to make up for how awkward it is to aim with console controllers. It was far less widespread in 1989, making Prince of Persia a somewhat unusual game where a klutz could pull off heroic stunts, unlike the typical fare where you accidentally step into knee deep water and drown.

Level 1: Sword (Cell)

After escaping his cell through a loose tile in the floor, the player will walk to the right and hit a dead-end, in the form of a guard. In the frame story, the prince was imprisoned by the evil vizier - it becomes evident that he wasn’t allowed to keep any weapons, and he cannot defeat this guard unarmed. Mechner’s design incepts two questions into the players mind: (1) what is behind that guard? and (2) how can I get past him? These two questions motivate the player's exploration of the rest of the level, and makes actually finding a sword much more meaningful (in case finding a sword wasn't exciting enough, in and of itself).

Mechner makes extensive use of this one weird trick to engage the player: he shows you something you want and makes you work to get it. The same first level could have been designed where the reverse sequence would be more natural or even enforced: first finding the sword, then encountering the guard. Allowing the player to try to bypass the guard just presents a false choice, in terms of gameplay. But the feelings of agency and accomplishment are much stronger when the player is first allowed to fail, and then to solve.

Level 2: Normal (Guards)

This level has a fair bit of jumping and swordplay: fun to play, but otherwise unremarkable.

Level 3a: Gate (Newskel)

Do you know that scene where Indiana Jones rolls under a door just before slams shut, almost leaving his whip behind? So does Jordan Mechner, and this is why this part of the level exists.

The setup is a button that opens a gate three screens away. Soon after pressing it, primitive PC-speaker sounds start ticking, emphasizing the time pressure: slowly, the gate closing back shut. If the player keeps a reasonable pace, he will find the gate just as it is already half closed and realize that he has no time to think. After a perfect running jump, the prince will be left hanging by his fingers beneath the gate, just barely in time to heave himself up and crawl in under it before it closes. Phew, that was close!

This scene would not work without the forgiving input buffers that makes it reasonable to demand that the player makes a max distance jump. In Mario, with its freer movement requiring more precise timing, any given distance would either be trivial for good players or overly frustrating for less experienced ones.

Two additional elements are worth pointing out: the falling floor tile and the spike trap. These are irrelevant in terms of gameplay, but they serve a much more important function: they add to the chaos that, like special effects in movies, makes the scene feel packed with action.

Level 3b: Skeleton (Newskel)

It is actually trivial to reach the exit of the level just by going left right from the start, but it is closed: the screen with the exit even shows the button that opens it. Mechner, knowing that challenge is what makes a game, has placed it out of reach for now, requiring you to take the scenic route that culminates with the gate jump.

After finishing the first half of the level, this button is easy to reach. Almost too easy. Previously, getting to the exit once it is open has been a formality, and this level seems to follow the same pattern, until a previously inert pile of bones suddenly springs to life and brandishes a sword in the prince’s face.

You are now fighting for your life, and while this is happening you need to realize that the skeleton doesn't have a life bar, so you can't just stab it to death like with the normal guards. Furthermore, you are fighting on an open-ended platform - if you retreat too far, you will fall to your death. The solution to this mini-puzzle is to force the skeleton back and off the other end of the platform - it doesn’t take a genius to figure this out, but by forcing you to come up with this solution in the middle of a swordfight, Mechner conjures tension.

Level 4: Magic mirror (Newmirror)

The first striking feature of this level is the new tileset: instead of the drab, gray blocks of the first three levels, we now are in the same luxurious surroundings as shown in the princess’ quarters in the intro. Are we getting close? Actually, no, but that’s what we’re supposed to think.

The very end of the level introduces a new subplot. The prince must go into a cul-de-sac to open the level exit, but on his return he will find that a mirror has mysteriously appeared and blocks his way. This is Mechner's one weird trick in action - an obstacle is so much more meaningful when you’re already craving what’s behind it.

Some trial and error will reveal that the prince can jump through the mirror, but not without consequence. His shadow will split out of him (!) and exit the stage in the opposite direction, leaving the prince himself with only the last sliver of his health remaining.

Having the mirror harm the prince is an interesting design - it turns out to be completely inconsequential, because all that remains of the level is some peaceful jogging. It nonetheless adds tension and communicates to the player the trauma that the prince suffers from having his soul split in half.

Level 5: Thief (Thief)

The set piece of this level also gives it its name: the prince will eventually come to a screen with a big red power-up potion at the end of an obstacle course. While making his way towards the prize, his shadow from the magic mirror in the previous level appears and steals the potion away from right under the prince’s nose. While we still know little about this mysterious shadow, he is now firmly established as an assh- antagonist.

Before the start of the next level, there is a very short cutscene showing the princess watching the sand running through the hourglass, representing Jaffar’s ultimatum drawing ever closer: Marry him … or die within the hour.

Level 6: Plunge (Plunge)

In terms of gameplay, what stands out in this level is the guard who is unusually fat and also an unusually good fighter, letting the game show off its beautiful animated strike-and-parry sequences. However, the level is not named after the fat guard, but rather its key narrative element: the level ends with the prince making a max distance running-jump, leaving him hanging off of a ledge by his fingers.

The problem? The shadow waits menacingly behind the gate. This time, he ruins our progress by taking a single step forward, shutting the gate in the prince’s face and leaving him no way up, forwards or back. No way, other than plunging down.

To emphasize the setback this represents, the level tileset changes back to the “dungeon” tileset of the earlier levels. If you didn’t already hate the shadow for stealing your potion, you now have every right to want to murder him.

Level 7: Weightless (wtless)

Last level ended with a fall, so that is how level 7 starts. Absent player inputs, the prince will plunge half a dozen floors down and find himself lying dead right in front of the exit gate. Holding a button is all it takes to grasp hold of a ledge, but the rest of the level holds plenty of challenge. Some exploration will quickly reveal a mysterious green potion, well out of reach for now. Curse you and your one weird trick, Mechner!

A lot of platforming later, the prince has looped back to reach the green potion. Drinking it will allow him to float down and land gently in front of that same exit gate. This is the end of the level, unless the player lets his curiosity get the better of him and explores past the button that opens the end gate. Two things will happen: (1) he will find a big red potion (yay!) and (2) unless he is very fast, he will be stuck behind a closed gate (curses!). That’s what you deserve for losing sight of what should be your first and only priority, namely rescuing the princess.

Level 8: Mouse (329)

Occasionally between levels, there are very brief cutscenes showing the princess in her chambers, watching the sand running in the hourglass that represents Jaffar’s ultimatum. For this cutscene, however, the princess is not content to simply wait to be rescued: she is instead shown dispatching her white pet mouse to search for the prince.

The start of the level features an extremely defensive guard - unlike all other guards in the game, he will never advance into striking range, instead preferring to wait for the prince to come to him. In terms of gameplay, this is somewhat interesting - the easiest swordfighting strategy for most players is to stand back and react to the guard stepping forward. There is a foolproof advance-parry-strike sequence that can be used, but it’s not as simple as wait-strike and requires more precision.

Because of Mechner’s dramatic flair, this highly defensive guard has been placed with his back against a two floor drop. And because the guard is so unwilling to advance, it is quite likely that the duel will end with you pushing the guard back and off the edge. For good measure, the bottom of the drop is a spike trap, resulting in the guard being impaled on spikes in the style of Mortal Kombat’s fatalities.

This is, however, not the centerpiece of the level: Level 3 surprised the player with a skeleton after opening the exit gate. Level 4 featured a magic mirror, and level 7 had the big red power-up honeypot. Level 8, forcing the prince to slow down with a series of tricky obstacles, traps him behind a shut gate with no way out. The game affords the player just enough time to rush through the five stages of grief: Curse you, Mechner! Has the hero reached the end of his journey?

But then, as the player is coming to terms with acceptance … just then, the princess’ white mouse comes to open the gate that he is trapped behind, greet the prince by standing up on its hind legs, and then scurry away. The rescuer becomes the rescued!

Another cutscene after the level shows the mouse returning to the princess’ chambers and her patting it on the head. Bless you, Mechner!

Level 9: Puzzle (Twisty)

This level reuses a similar running-jump setup as level 3, but without the time pressure, and it features a clever puzzle where the player will find himself blocked at the very end of the level unless he has made an unstable tile drop down - it will land on top of a button and keep its corresponding gate open indefinitely. It’s probably easier to solve this puzzle on accident than on purpose, but to the game’s credit, the function of the button is clearly demonstrated when the player inevitably passes it. The hard part is noticing.

Level 10: Sneaky (Quad)

Level 10 is named after the four gates in the first screen of the level. Its most standout feature is a puzzle where a guard stands on top of a ledge. If the prince climbs up, the guard will one-hit kill him before he has time to defend himself.

The solution is obvious in hindsight and altogether fair - the guard turns around to face any loud noise, such as running. The prince must simply have him face away from the ledge, and then walk quietly to sneak up on him from behind. With the element of surprise on his side, it is the prince who gets to one-hit kill the guard.

Level 11: Unstable (Wild)

Half of the level is unstable floor tiles, giving it a very chaotic feeling, but we have to move on.

Level 12: Shadow (Tower)

The penultimate level features the most challenging platforming in the game, as well as a devilish puzzle that concludes the subplot that is almost forgotten by now. After ascending the tower-like structure of the level in a challenging sequence of climbs and jumps, the prince will enter a screen showing a sword lying innocuously on top of the whole tower. One weird trick applies, of course: the sword is firmly out of reach, for now.

Some additional platforming allows the prince to enter this screen from a different direction, but - surprise! The sword is gone. And there’s also a second lifebar visible in addition to your own, but no enemy in sight. Ominously, this second lifebar has the same color as that of the prince himself.

When the prince advances to where the sword used to be, none other than the shadow drops down from above, and you both draw your swords. Finally, it’s time to show this guy who’s the swordsman and who’s the pincushion.

There’s only one problem: the shadow is you. If you hit him, you both take damage. You will normally have more hit points than him, which seems like it would allow you to kill him first, but you will immediately drop dead as if your astral cord was severed. Because of some falling tiles, you cannot even try to push him gently down the single floor drop where you climbed up. If you feel creative, you might try to push him off the tower, but it turns out that falling fifteen floors is also fatal to the shadow, which in turn kills you.

We have arrived at an impasse. Curse you, Mechner!

The solution turns out to be a move that has been available, but worse than useless, for eleven levels. Pressing down while fighting will sheathe your sword, which only really happens on accident and invariably leads to a guard delivering a coup de grâce straight to your face. But the shadow, as his origin story would suggest, will mirror this move: with the both of you unarmed, you can finally embrace. The prince, long divided, must unite.

You even get back that extra hit point that he stole from you in level 5, which is a cute touch.

Level 13: Jaffar (Final)

Level 13 is short, features some simple platforming and a satisfying duel with Jaffar himself. This is easily the most difficult swordfight in the game, with a pinch of extra drama delivered from a loose floor tile that leaves the prince fighting with his back against the abyss. Somewhat disappointingly, there are no extra bells or whistles to this fight: it is very similar to the halfway fight in level 6 - Jaffar is just a stronger guard, albeit with a gray beard and a cool cape.

Level 14: Princess (Victory)

Level 14 has no proper gameplay, it only consists of running through a few rooms and gates, using the nicer, luxurious palace tileset instead of gray blocks of stone. The last screen change cuts seamlessly to the princess and prince embracing, finally reunited. In tune with Mechner’s fascination with movies, including Disney, the princess’ mouse (your little helper in level 8) shows up too. The game ends with a screen of text bookending the story: Jaffar is defeated, the people rejoice, the people hail the player character as no longer a stranger but rather The Prince of Persia.

Bless you, Mechner.

The Journal of Persia

It was the start of a journey that would see my shape-shifting prince transform into a modern video game hero, LEGO minifigure, and even Jake Gyllenhaal in a summer blockbuster movie. But in 1985, he existed only as a few scribbles on a yellow-lined pad. In my old journals I recorded his birth pangs.

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 2). Kindle Edition.

Do I really want to make another game?

May, 1985, New Haven. Jordan Mechner has just finished his psychology degree at Yale. His grades have been somewhat lackluster and he is trying to decide on a trajectory for his life after college. Strangely enough, he has managed to land himself in a position where the most responsible choice would be to go into video game design. Yes, really.

During his years at Yale, Mechner made his first commercial game: Karateka for Apple II, published by Broderbund. It happens to be topping the Billboard software rankings right as he is graduating. Not bad at all for a college student's side project, and definitely part of the explanation for his grades. Karateka is going to keep earning him significant royalties for years to come, allowing him to take on his next project without any advance.

Broderbund would be more than happy to work with Mechner on another game - ideally a sequel to Karateka - so there's only one problem: He isn't really sure if he wants to go on making video games. His great passion is movies, which has also been distracting him from his coursework, and now he’s worried that continuing with games will just be a way to give himself permission to put off the hardships of trying to break into the world of filmmaking.

While screenwriting is pulling him away from starting on a new game, there is also a push-factor: the idea of sitting himself down to code makes him anxious. Like a woman who has just had a child, Mechner remembers the trauma of giving birth to Karateka. He knows that for every night of creative design and storytelling comes nine nights of lonely, grueling programming. He doesn’t seem to be doubting his own technical acumen, as much as he is questioning whether he wants to make a new game enough to push himself through all this work.

Despite all these doubts, Mechner lands in Los Angeles one year later to make Prince of Persia. In his luggage is a contract for 15% royalties and videotaped footage of his brother running, jumping and climbing. Oh, and also a highly unrealistic timetable:

“I figure it’ll take me a year to do the game, (...)” (p. 22) Kindle Edition

The man who chases two rabbits

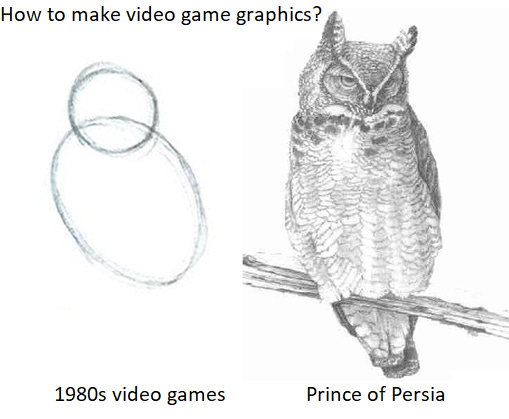

September, 1986, Los Angeles. Having installed himself in the Broderbund offices, Mechner puts in some solid work on Prince of Persia. His first challenge is to get live action video from analog tape (remember, this is forever ago) into his computer. Mechner’s vision is to make a game that bridges the gap from the very primitive graphics of games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man that sort of help you imagine whatever they are supposed to represent, to lifelike animations with a feeling of weight to them that include the rest of the fucking owl.

To achieve this effect, Mechner employs a technique called rotoscoping, which basically involves going through video footage frame by frame and tracing the outlines. It is well-known in the world of filmmaking, for instance from Disney’s animated movies, but not very practical for video games, both because of the additional work that goes into digitizing and the unforgiving memory limitations of the computers of the time.

Mechner runs into a series of technical issues with getting sufficient contrast in his images to enable him to automatically read them into the computer. In desperation, he resorts to buying a very expensive piece of video equipment with a credit card, using it and then returning it for a full refund.

In the middle of this, Broderbund moves offices. Mechner succumbs to the temptation of trying to work from home and starts slipping back into his recurring habit of procrastination. Some things never change.

It is in May, 1987 that disaster strikes:

BIG NEWS. Virginia Giritlian of Leading Artists called to say she loved my script. She’s given it to her boss Jim Berkus to read and will get back to me in the next couple of days.

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 44). Kindle Edition.

A few months later, Mechner comments that it would be ideal if he could finish the game, achieve some kind of closure and devote himself 100% to screenwriting. He spends his time meeting agents, writing and rewriting scripts and getting strung along with non-committal offers until a string of rejections cruelly wakes him from his world of dreams in the beginning of 1988:

On impulse, more to escape cabin fever than anything else, I drove into Broderbund and actually put in a full day of work (...). I was startled to realize that the most recent code printouts in my folder are dated March 26, 1987. (...) What the hell have I been doing for eight months?

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 51). Kindle Edition.

Soured by his failed love affair with screenwriting, Mechner firmly sidelines his mistress and returns to Prince of Persia with the full attention of an affectionate husband. It is startling how close the game came to being canceled before it was saved by a handful of producers rejecting Mechner’s scripts.

A week ago, I’d pretty much given up on the game. I only had to take the final step - a formality, really - of informing Ed that the project was dead.

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 57). Kindle Edition.

Behind every successful man is a woman

June, 1988. Prince of Persia is at least a full year behind Mechner’s original timetable. Time and time again, we get examples of how different Prince of Persia was in the earlier stages, and how crucial Tomi Pierce was to him getting it right. She was a colleague at Broderbund, working on educational games, as well as a personal friend of his. They would later go on to collaborate on a game called The Last Express.

Roughly two years into development, Prince of Persia has no enemies. Mechner explains that the elaborate animations for the prince don't leave enough memory in the computer for any additional characters. Pierce suggests the common workarounds, basically reusing the prince’s animations with small changes, but Mechner thinks that the prince has too much of a cute feel to him for this to work well. Pierce persists, convinced that the game needs more conflict and combat, until Mechner comes up with the idea of using a combination of bit-shifting and XOR to create a ghostly counterpart to the prince.

Thus the shadow is born, not from any sort of artistic vision, but simply from trying to circumvent the technical limitations of the Apple II. Restrictions breed creativity, as they say. Pierce baptizes the new antagonist Shadow Man: within the day, Mechner has the animation implemented in code. Another colleague seeing Mechner’s demo comes up with the idea of the magic mirror (level 4), and the full shadow storyline concluding with the melding (level 12) is hammered out immediately.

“You’ll sell a billion copies,” Tomi predicted. (p. 62) Kindle Edition

Gradually, time is beginning to catch up with Mechner. Royalties from Karateka, his only revenue stream, is beginning to dry up. Worse yet, the market for video games for Apple II is looking increasingly barren - the system is more than ten years old by now, rapidly losing market share to PC, Amiga and Nintendo. The game needs to ship: ideally yesterday. Pinned by Brian, he commits to a QA-ready version in eight weeks.

At the same time, his game is not actually working as a game. Within three days of journal notes, Mechner identifies the problem in excruciating detail:

“I like games where you can shoot things. Your game has no rewards except getting to the next level. It’s all survival and no triumph.” - Tomi

She’s right about POP. It’s empty and lifeless. I don’t know if even the shadow man and swordfighting will change that. (...)

What is the point in running, running to get to the exit, if all it gets you is more of the same? (...) What makes a game fun? Tension/release, tension/release. (...) Running, jumping and climbing, no matter how beautifully animated, hold your attention for maybe the first three screens. Then you start to wonder: when is something going to happen? (...) There needs to be sub-goals. Places where you can say: “Whew! Did it! (...) What’s next?”

If the sub-goal is “solving the level”, you need a consistent visual indicator of how close you are. You don’t just stumble on the exit. (...) That’s why collect-the-dots games like Lode Runner and Pac-Man always show the entire screen at once. (...) But POP doesn’t. (...)

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 68-72), excerpted. Kindle Edition.

Mechner is not content with identifying problems: he simultaneously lays out his solutions, which deserve a massive block quote. Here, we can get a glimpse of the thought processes that enabled him to make a fantastic game, including his conscious awareness of what I have been calling the one weird trick:

How can I be so up on screenplay story structure, and so blind when it comes to my own games?

A story doesn’t move forward until a character wants something. So - a game doesn’t move forward until the player wants something. Five seconds after you press start, you’d better know the answer to the question: “What do I want to happen?”

There always has to be a range of possible outcomes, some better than others, so you’re constantly thinking: “Good… Bad… Terrible.” Every event has to move you closer or further away from your goal, or it’s not an event, it’s just window dressing.

The overall goal of POP is to get the girl. But that’s not a strong enough magnet to pull the player through all that distance. It needs sub-goals.

Beating a guard in Karateka buys you time to gain distance. You want to get closer to the palace because the princess is there; every guard you beat brings you closer. It’s simple, but it works. In psychological terms, it even follows the classic addictive pattern of diminishing rewards: each subsequent guard is harder to kill, and gives you a smaller reward for your pains, until you reach the intermediate goal (the end of the level), at which point there’s a bigger reward, and things get easier again… for a while.

Getting through a dungeon in Prince of Persia doesn’t give that satisfying feeling of getting closer to the goal. Partly because it all looks pretty much the same. That, I can fix.

But there’s another key element in the story structure that also applies to games, and is missing from this one: The Opponent. Someone competing for the same goal as the hero, or trying to stop him from attaining it. The more human, the better. (The days of Asteroids and Pinball are over.)

In this case (we’re short on time, so let’s use the opponent we’ve already got), it’s Shadow Man.

Some games boast a whole series of different opponents. (According to Truby, this is characteristic of Myth, and it weakens the story.) We’ll make the shadow man your opponent for the entire game. You’re competing for hit points. Each blow you deal him weakens him. Each power dot you eat makes you stronger. But if he gets there first and he eats it, he gets stronger. So when you face each other with crossed swords, the balance of power is not predetermined (as in Karateka), but is the result of your own actions thus far in the game.

It links the combat with the running-around. It’s brilliant. I love it!

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 72-74). Kindle Edition.

Mechner was originally envisioning a game resembling Lode Runner, heavy on exploration and difficult puzzles across 50 (!) levels and with no combat whatsoever. Swordfighting, probably the most memorable part of the whole game, edges its way into the game in the final months of 1988. Mechner’s pivot from puzzles to action and narrative reorients the entire game. In his own words: Ten easy levels. You start in the dungeon, you end with the princess. (While this is pretty much the final state of the game, he still hasn’t actually committed to this idea: instead he is playing around with a Mario-like design: Your princess is in another castle!, with four increasingly difficult sets of levels.)

So there it is: Slap a story frame on it. Add combat. Design ten easy levels. That’s Prince of Persia. The rest is a bonus.

The Making of Prince of Persia (p. 77). Kindle Edition.

Mechner ends 1988 with a New Year’s Resolution: Finish Prince of Persia by July, 1989. With swordfighting in the game, which looks great and feels fun, he is now once again convinced that his game is going to be the greatest of all time.

Tomi was right all along. “Combat! Combat! Combat!” (p. 80) Kindle Edition

I’ll put in the little white mouse because I said I would, and because I’’ll never hear the end of it from Tomi if I don’t (...). (p. 105) Kindle Edition

Man never is, but always to be blest

From 1989 and on out, things are falling into place. Mechner works long days converting visions and sketches to working game code as well as sanding down all the rough edges. The skeleton (level 3) is briefly mentioned. Tina LaDeau, the eighteen year old daughter of a co-worker, is invited into the offices to serve as reference for the princess’ animations in the game’s intro and outro. Mechner comments on her beauty in the journal on multiple occasions: She’s a fox and It’s a drag, having to spend hours reviewing video footage of this girl in slo-mo and frame-advance, but these are the sacrifices I have to make to get this game done. Remember, he’s just 25 years old and he was writing a personal diary he could hardly expect would end up getting published.

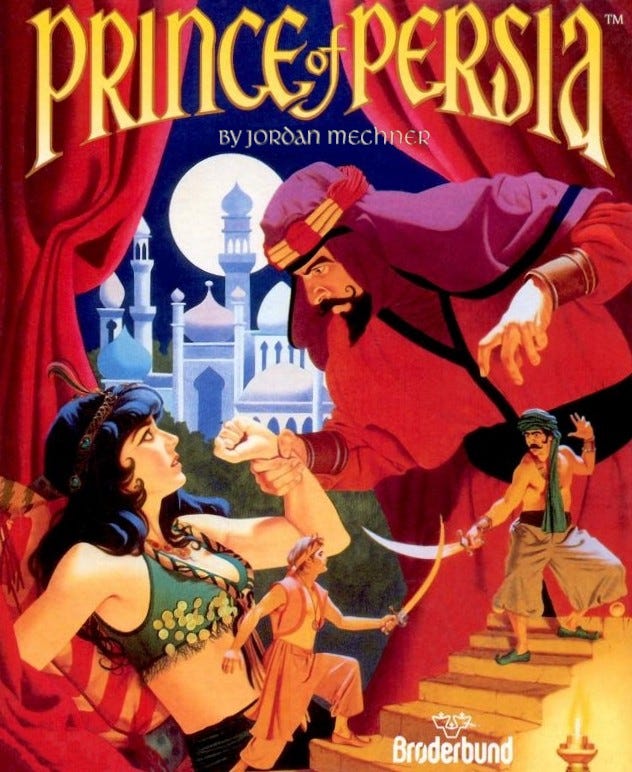

He has to deal more and more with teams of people - designers, marketers, programmers. This mostly seems to irritate him, partially because these people fail to do what he wants them to do, but also (mostly?) because he can sense that his own soft skills are holding him back. The women in marketing get lambasted in particular, both for not putting enough of a push behind a game with enormous potential and for censoring the box art by requesting an extra layer of “sports bra” under the princess’ top.

Various technical issues and small arguments notwithstanding, the overall story is that the game is finished, universally lauded and ultimately very successful despite a bit of a rough start. The game is so captivating that it doesn’t need a carefully engineered marketing push to pick up steam: despite launching on a heavily outdated platform, there’s no force greater than word-of-mouth.

Broderbund starts talking about sequels and Mechner starts thinking about screenwriting. Having become somewhat wealthy and a minor celebrity, he decides to go hands-off on Prince of Persia 2, contributing on the design remotely while going off to live in France, studying filmmaking at NYU and eventually, making a documentary film in Cuba and writing a graphic novel.

Why? I’m not a psychiatrist, so I don’t exactly have a qualified opinion, but it also means that I can happily speculate on Mechner’s psychology without running afoul of the Goldwater rule.

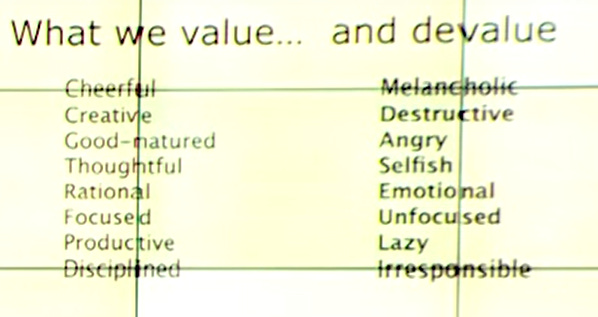

Mechner held a talk at Gamelab Barcelona in 2015, ostensibly about Prince of Persia, but mostly about his own psyche, called The Shadow and the Flame: Facing our Dark Side in Video Games and in Life. In it, he talks about the shadow, both as it appears in Prince of Persia and as a concept from Jungian psychology. During socialization, he explains, we learn that certain parts of ourselves are impermissible and we fragment ourselves into an ideal, conceptualized as our true self, and a shadow, the parts of ourselves that we reject out of necessity. We try to suppress our shadow, but like in Prince of Persia, the shadow is us and whatever harm we do to it, we must suffer ourselves. We cannot find peace while living at war with ourselves - we must, like the prince, sheathe our sword and embrace the shadow - not capitulating to it and not succumbing to our vices, but accepting it as a valid part of ourselves.

In Facing our Dark Side, Mechner talks about how he was feeling down in his year off after his success with Prince of Persia: “Actually, I wasn’t having that much fun. (...) It’s as if there was some voice inside me, that didn’t want to celebrate, that didn’t want to feel, you know, like a big shot. (...) I was a little bit embarrassed that I hadn’t had a better time. (...) There was something inside me that year that made me feel like this was not the time to celebrate, this was not the time to have fun, that what I need was not to be raised up, but to be cast down.”

Jordan Mechner - or at least that version of him that I imagine that I know through his journal - is brilliant and ambitious. His problem is that the only thing he craves more than success is failure. While making Prince of Persia, particularly in the first few years, he constantly flip-flops between thinking he is making the greatest game ever and despairing that in the unlikely case that he manages to finish the it, it won’t make any difference because it wouldn’t be any fun anyway.

For whatever reason - going by his Gamelab talk, perhaps there is a Renhcem running around stealing his big red potions - Mechner has such an overwhelming sense of ambition that he cannot help but chase after success, but like a dog chasing a car in the streets, it doesn’t do him much good to actually catch it. Having become a star video game designer, he shies away from that business to study film and make niche documentary movies. When returning to video games, he makes an experimental story-based game in his own independent studio along with Tomi Pierce. Perhaps, like a gambler, it is not really about the winnings, but about that feeling of balancing on the cusp between triumph and tragedy. Perhaps it is that he feels like he has so much to prove that having a clear path towards success is not good enough, but that it is only beating the odds that tastes like victory.

Regardless, we must hope that he has made peace with his shadow in the intervening years.

Sometimes I like to get ice cream, just for myself, and I don’t bring it home to the family, and I don’t tell them that I went and I got an ice cream. It’s amazing how happy that makes me feel.

Jordan Mechner, The Shadow and the Flame, Facing our Dark Side. Timestamp: 1:01:19.

Aeternitas longa, ars brevis

Full disclosure: while I’m not actually Jordan Mechner, I am most likely wearing nostalgia goggles. Prince of Persia was one of my childhood games. I replay it every once in a while, perhaps every five years, and it keeps striking me as a beautifully simple and wonderfully clever game. Usually, what I appreciate in a game is the complicated interactions with deep strategic implications. Prince of Persia is in many ways the opposite, offering little strategic depth, but dozens of tense and satisfying scenes.

Nonetheless, the old Prince of Persia game is for all practical purposes a relic of the past. It lives on in the minds of those who played it decades ago, but it fades into obscurity one funeral at a time. And while this is inevitable for a game designed to fit within the technical limitations of a bygone era, it feels deeply unjust. Prince of Persia is a masterpiece. It has so much to teach about the intersection between storytelling and video games. It seems cruel that this piece of art, by virtue of being a video game, must die so young: that it is torn from us, while plays and symphonies and novels are afforded eternal lives.

So in a sense, this review is my attempt to preserve a part of its essence. Not the butterfly itself, alive and fluttering its wings, but at least the form it has left behind, pinned with a needle and put inside of a frame.

And in a sense, all of art is ephemeral, only on different time scales. Self-referential memes and parodies have the shortest shelf lives, but paintings fade, buildings crumble, and even digitally preserved text loses its meaning over time as the cultural context changes. We already struggle to appreciate the Iliad’s grounding in Greek mythology or even to empathize with the constant, ravenous hunger of the children in Charles Dickens’ novels.

There is a ritual in Buddhist temples in Tibet, of painstakingly creating elaborate pieces of art from grains of colored sand, but then destroying them immediately upon completion. I don’t know if this is the intended significance of the sand mandalas, but I like to think of them as a reminder that everything that is put together must eventually come apart, and an encouragement to accept this. We can, in a sense, think of this as the shadow of art - we should strive for longevity, but if we try to impose permanence on art, we condemn ourselves both to a futile struggle to preserve and an unending mourning for what has been lost.

And somewhat strangely, there is consolation to be found in this: that nothing is forever: All go to one place; all come from dust, and all return to dust. For if this constant churn of entropy and creation is simply the natural order of things, then there can be no injustice.

This is Tomi Pierce. [Slide: picture of her riding a horse. Caption: Tomi Pierce (1953 - 2010)] She passed away five years ago. I just want to take this moment to acknowledge her contribution to those games - and to my life. She was my best friend and I really miss her.

Jordan Mechner, The Shadow and the Flame, Facing our Dark Side. Timestamp: 0:53:24.

Resources and further reading

Talk by Jordan Mechner: Jordan Mechner: The Shadow and the Flame: Facing our Dark Side in Video Games and in Life

Text interview with Jordan Mechner: The DeanBeat: How Jordan Mechner shepherded Prince of Persia across 30 years | VentureBeat

The story of Prince of Persia’s box art: How Prince of Persia's box art unexpectedly contributed to its success

Tomi Pierce’s obituary: In memoriam Tomi Pierce | Facebook

Current speedrun world record: Prince of persia speedrun any% World Record in 12:20.00 by higlak

Complete pacifist playthrough: Let's Play (Pacifist) Prince of Persia 1 (DOS)

Jordan Mechner’s YouTube channel, including a number of behind-the-scenes videos: Jordan Mechner - YouTube

Endnotes

The Game of Persia: I use the nicer and more familiar 1990 DOS port of Prince of Persia for all the screenshots and GIFs. This particular port was developed and published by Broderbund, under Mechner’s oversight, and is according to him the “definitive” version of the game.

GIFs, techinal: The GIFs have actually been through an elaborate chain of processing, from video capture in a DOSBox clone, reencoding from the strange format produced by DOSBOX to AVI using VideoLAN, reencoding from AVI to WebM to GIF using various Python libraries. WebM isn’t compatible with Google Documents (which is a bit insane when you think about it), converting straight from AVI to GIF gave palette bugs (there are still some in Level 14, but it was much worse originally), reading the DOSBOX compressed video directly wasn’t possible with OpenCV. The above conversions don’t properly conserve frame rate: ad hoc downsampling gives some minor artifacts and the GIFs play a fair bit faster than the in-game speed. The progress bars have been added manually.

The Game of Persia, section: On purpose, I wrote this whole section before reading Mechner’s journal. I was prepared to do heavy editing, combining my own misguided guesses about design intent with the authoritative truth from the horse’s own mouth. It turned out to be unnecessary - practically everything I was tempted to “read into” the game is actually backed up by the journal.

The Game of Persia, introduction: The input buffers may have been introduced to work with the realistic animations in the game. Mario allows the player to jump whenever he feels like, but Prince of Persia has to line up the start of a jump with the actual steps of the running animation.

Levels: I have renamed the levels: Mechner gave them names that are only used in the game’s internals and that are never exposed to the player: some of these are abbreviations or codes. Mehcner’s names are given in the parentheses.

Level 1: There are actually two different sequence breaks in this level. It is possible to lure the guard forward and circumvent him by doing a second loop through your starting cell. It is also possible, with extremely precise timing, to simply jump past the guard unarmed. In either case, the prince will start the next level with a sword, regardless of whether he actually found it in this level. The first of these sequence breaks is probably intentional, the second almost surely not.

Level 2 and many other levels: There are more or less well hidden big red power up potions scattered throughout the levels. These are generally placed in a way that incentivizes extra risk or clever exploration. For the sake of brevity, I have omitted most of them.

Level 3: Mechner shows this clip from Indiana Jones during his Gamelab talk.

Level 3: The only real justification for splitting level 3 into two halves is the existence of a respawn checkpoint after the dramatic gate jump. Aside from this, there is only a single level: the two unrelated narrative highlights makes this splitting in halves extra convenient.

Shadow, formatting: I recently read House of Leaves and shameless copied this formatting antic. Unfortunately, the dark purple coloring didn’t survive migration from Google Documents to Substack, and the bold-italics stand a bit too much out from the background.

Level 5: The thief scene has a quite ugly design flaw. The timing of the shadow drinking the big red potion does guarantee that he will steal it from the prince: however, if trying to go as fast as possible, the prince will actually be able to catch up with and pass/clip through the shadow. Nothing really happens, but it looks like quirky and unintended behavior, and undermines the mystique of the shadow and particularly the moment in level 12 where the prince merges with the shadow. If the two can merge like this, why doesn’t this happen already here?

Level 7: It is possible to redo roughly half the level after getting stuck at the big red potion. The green feather fall potion will be gone, but you can survive the drop without it by hanging from the ledge. However, this presents many extra possibilities to mess up and die. Most players will simply find themselves punished for their greed. It is also possible to reach it from a different direction by carefully mapping the level or making a leap of faith.

Level 8: In a tweet, Mechner says that he doesn’t remember what this cryptic name signifies. His best guess is that it is simply a date: perhaps he designed the level on the 29th of March. These level names are never exposed to the player: they exist only in the game’s internal data structures and developer’s documentation.

Level 8: While it takes some serious speed, it is entirely possible to get in and out of the dead end before the gate closes, such that the mouse’s help isn’t needed. In particular, it requires you to be very comfortable with the timing of the chompers (Mechner calls them slicers in his journal).

Level 12: The shadow happens to have exactly 4 hit points, which matches the prince’s starting 3 plus one from drinking a big red potion. Coincidence? Maybe, but why ruin something beautiful with skepticism.

Level 13 & 14: In game, these are numbered as level 12; the whole tower climb, shadow fight, Jaffar fight and approach the princess’ chambers is conceptualized as a single level but programmed as 3 distinct levels.

Do I Want to Make Another Game: Karateka was Mechner’s first published game. He made a number of other games earlier on, essentially growing up with an Apple II.

The Man Who Chases: Baghdad was Mehcner’s original working title for the game, used in the journal. Ed Badasov at Broderbund came up with the Prince of Persia-name, originally as another working title, which eventually became the actual name of the game.

Behind Every Successful Man: Mechner will later find a proper solution to the memory limitation that allows him to fit in the normal guards and swordfighting that are in the game.

Man Never Is: The “sports bra” was added on top of the original box art to make the image a bit less risque. It is a thin, brighter green line added inside of the rest of the top. Details and a bigger image can be found under Resources and further reading.

Aeternis Longa: All go to one place… is Ecclesiastes 3:20.

Aeternis Longa: I must emphasize that Mechner’s journal is difficult to read, much more so than Prince of Persia is a difficult game to play and appreciate for a modern audience. It was not written to be published or really to be understood by anyone other than Mechner himself. Combining patience and familiarity with the source material, it is possible to find valuable insights into both how the Prince of Persia was made and how Mechner’s experienced this whole process. However, the journal does not do the best work of establishing context. Judicious use of search, both within the book and on the Internet, is recommended.

Changelog: I have made some minor changes to the document while migrating it to Substack, most of them by necessity due to different formatting tools.

Subscribe to When you scream into the abyss

For now a single purpose substack hosting a mirror of a submission to a book review contest.

Great write up for a great game! The sequel was also masterfully done. Albeit somewhat derivative

Thanks for the review! I barely played Prince of Persia myself but it came out when I got socialized with computer games, meaning I understand the constraints of the time. I am glad that you brought up the psychological element of the shadow - this was the one part of the game that I still remembered as special and deeper than just solving the puzzle.